As part of its commitment to address institutional racism and advance social equity, RISD is hiring 10 new faculty as part of a cluster hire initiative focused on race and decolonization in art and design.

Legacies of the Slave Trade

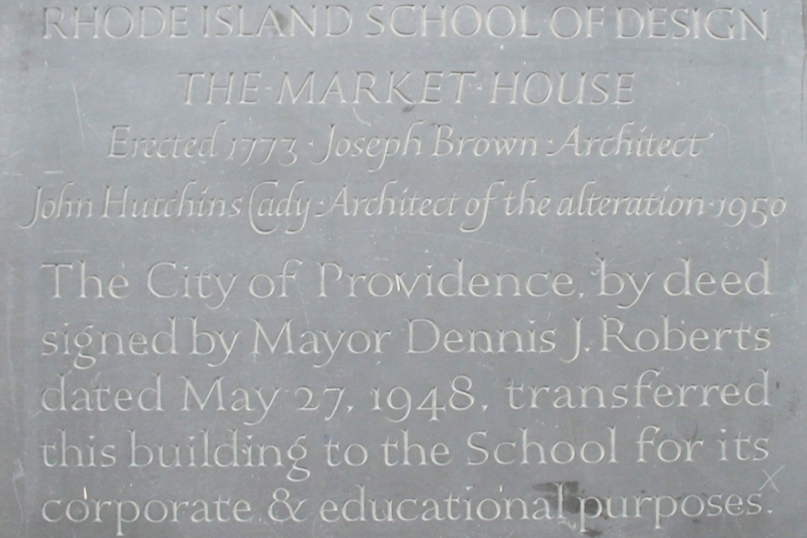

SEI Research Fellow Christopher Roberts studies cultural memory in relation to the history of Black peoples, with an emphasis on port cities in the US that anchored the transatlantic and domestic slave trades. Now in his second year at RISD, Roberts is researching the history of RISD’s Market House building and the surrounding area. Here he provides a sneak peek at the ongoing project and how it relates to RISD’s renewed commitment to combatting systemic racism on campus.

How is your research into Market House and Market Square shaping up?

I’ve spent a lot of time looking at the archival history, trying to determine what did or did not occur in Market House. RISD acquired the building in the mid 20th century. As the institution’s footprint has expanded, so has its legacies and histories. One of the stories I think Market House tells is how the histories of slavery and colonialism that emerged in and defined Providence are still with us today.

“One of the stories I think Market House tells is how the histories of slavery and colonialism that emerged in and defined Providence are still with us today.”

Does the idea that enslaved people were never sold on what is now RISD’s campus hold water, in your opinion?

The buying and selling of enslaved Africans touched the entirety of Providence, and RISD is part of Providence. It’s a bit of a stretch to say that none of these things were happening here, when there is zero doubt that they deeply impacted what was going on right up the hill at Brown University as well as in nearby cities like Newport and Warwick. Our circumstances are very different from Brown’s, given that RISD was founded after so-called Emancipation. But that doesn’t necessarily mean RISD isn’t implicated at all. Institutions can be implicated in a wide variety of ways.

You spoke in a recent panel discussion about Rhode Island’s huge part in the business of slavery: the ships and shackles. Is that what you’re referring to?

I borrow my understanding of the business of slavery from scholar Christy Clark-Pujara. What is now downtown Providence was in many ways a commercial hub. Rhode Island thrived off the transatlantic trade of goods and services, many of them directly tied to slavery: rum, molasses, cotton, textiles …

“For a very long time Black people have been tasked with proving their worth to society.”

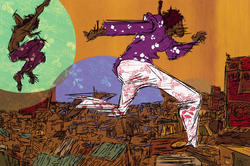

How does this research relate to the class you’re teaching this fall, Humanity or Nah?: Blackness, Gender, Resistance and Memory in Monuments, Maps and Archives?

For a very long time Black people have been tasked with proving their worth to society. One of the primary ways they go about making that argument is through an appeal to humanity: “I am like you. I am human, so I deserve not to be harassed or brutalized or killed.” But that argument is often posed to a society committed to not seeing those people as human, as valuable. So, the class questions whether or not people should continue to appeal to this thing called humanity or pursue other ways of being and relating to each other.

That brings to mind Black Lives Matter. Why do you think the movement is finally gaining traction now?

Institutions do not want to appear to be on the wrong side of history. That’s why you see everybody from Ford to Major League Baseball to Goldman Sachs doing Black Lives Matter stuff. I mean, everyone’s taking a knee now, but I’m far more interested in what happens when it stops being popular—when they may actually stand to lose something by advocating for social equity.

Do you feel that the institution is committed to change?

I am both hopeful and skeptical. RISD has been committed to a certain type of institutional whiteness, historically, and to move away from that after more than a century is going to take more than one year. It is an extremely uncomfortable and unsettling process because what you’re doing is asserting that Black and Brown people have knowledge and lives that are important and should no longer be marginalized.

“I see my position as a direct outcome of the Not Your Token protests that took place a few years ago and the continuing work of current students....”

What do you make of the idea of a cluster hire, in which a large group of scholars working on social equity are brought in together?

It’s going to be really interesting to see what types of support the faculty are met with when they arrive—not just at RISD, but at all of these institutions that seem to be opening their doors. Commitment means not just bringing these people in, but fiercely advocating for their presence. You have to believe that they are absolutely necessary to the institution’s relevance. And if we do not speak to the demands of our students of color, then we’re not relevant as an institution.

What role do you think RISD students can play in all this?

We need their creativity and imagination now more than ever, when people are questioning the role of law enforcement, what health care looks like, what justice looks like. Artists and designers are crucial. I see my position as a direct outcome of the Not Your Token protests that took place a few years ago and the continuing work of current students who organized risdARC [the RISD Anti-Racism Coalition]. More than their passion, which is evident, I am inspired by their work, their knowledge, their courage, their organization, their analysis, their power, their care for one another and their insistence on a meaningful art and design education.

—interview by Simone Solondz

October 9, 2020