SEI Research Fellow Nichole Rustin engages RISD students in contemporary political questions and develops their skills as liberal arts scholars.

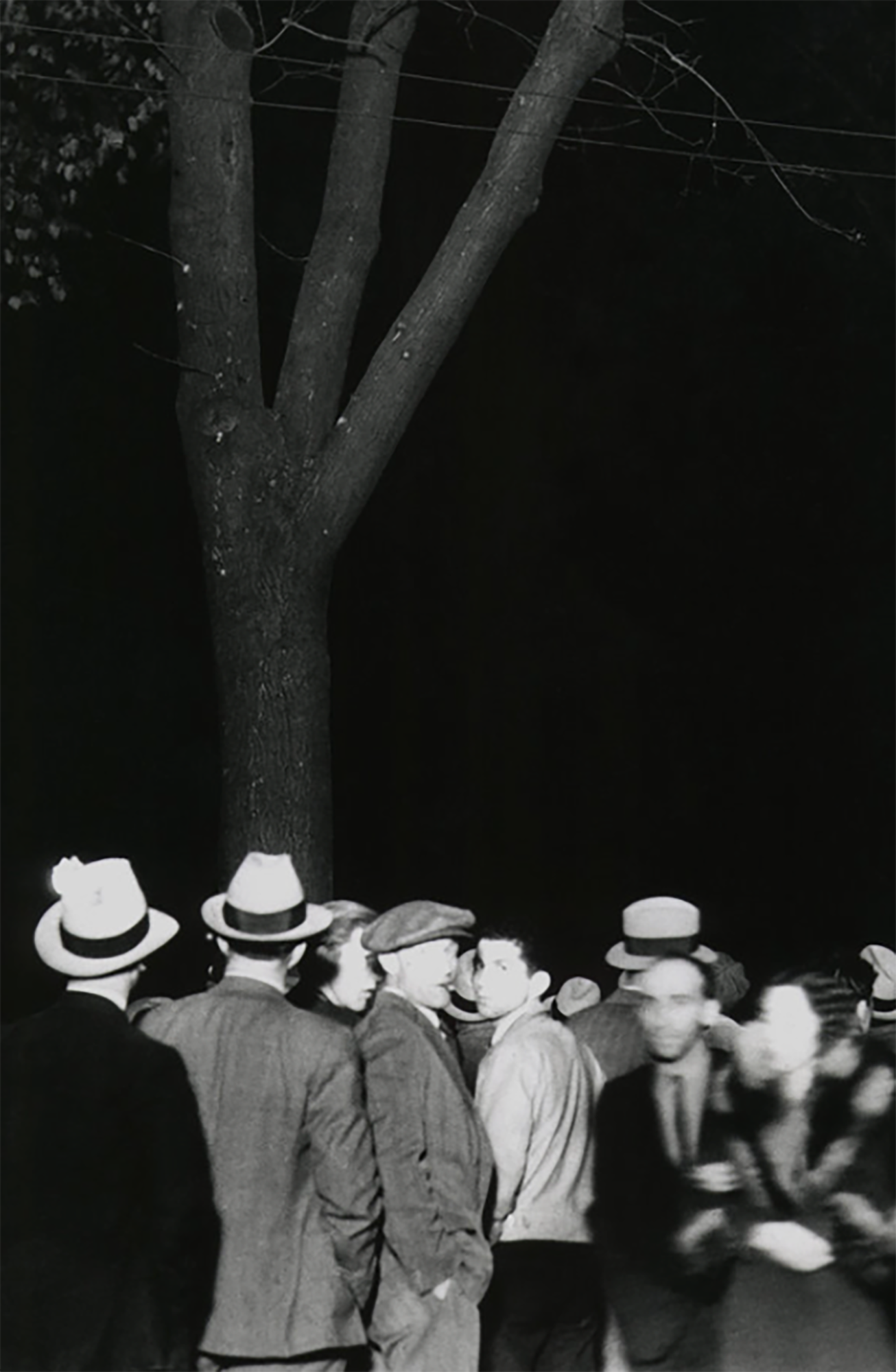

The Ethics of Bearing Witness

Recently hired SEI Research Fellow and Assistant Professor of Photography Zoé Samudzi studies genocide, race-making and visuality, the ethics of seeing/witnessing, biomedicalization and ancestry, the repatriation of art and human remains, and the spatialities of race and violence. The Zimbabwean-American writer and critic has published essays in Artforum, Bookforum, The New Republic, Art in America, The New Inquiry, The Architecture Review, SSENSE and elsewhere and was recently cited by Daily Show host Trevor Noah as one of the “brilliant, brilliant Black women” who have educated him over the years. Here she discusses the graduate-level seminar she just finished teaching in RISD’s Photography department and how working with image-makers is influencing her research.

What made you choose RISD as the next step in your scholarly journey?

A friend of mine was teaching architecture here and told me I should think about applying to RISD. Then I saw the SEI fellowship opening and decided to apply. I think a lot about the photographic image and really wanted to work with [Assistant Provost of SEI] Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa, whose work has meant a lot to me over the past couple of years. Now that I’m here, it feels like a good fit.

Stanley mentioned that you were teaching a graduate seminar called Looking at Violence during the fall semester. Can you tell me about that class?

A few years ago, I went to the National Archive in Armenia and started thinking about what it’s like for a nation-state to define its identity around genocide survivorship and how that shows up in Armenian visual culture. I was reading Susan Sontag’s Regarding the Pain of Others and thinking about the ethics of bearing witness. So, the class was inspired by that experience and considering the different subtexts around the production of battleground photography and other images of violence.

Painters, photographers, an architect and a graphic designer took the class, so it was exciting to structure these questions around all kinds of different visual practices. We thought about the history of the camera and the politics of color and looked at different moments in humanitarian photography: Armenia, post-World War II Germany, more contemporary atrocities like Hurricane Katrina and the famine in the Horn of Africa in the 1980s….

How does the class relate to the research you’re conducting as an SEI fellow, if at all?

I’m still figuring that out. Generally speaking, I’m interested in violence and how we have become acculturated to watching people die. I study genocide and think about community memory and how Indigenous communities—specifically the Ovaherero and Nama in Namibia—create their own grammars and cultural productions in order to understand and remember death. They’re not recognizable as genocide documentation because there is this kind of “absence” of photo documentation.

Is there a connection between your study of violent imagery and the Internet and social media?

Yes, absolutely. We see these violent images all over the place whether or not we want to. There’s an assumption that seeing atrocity will animate you to respond in some way. That’s the argument used by people who circulate body cam images of Black people getting killed. But at this point we’ve seen it so many times! When do we have enough evidence? How many images will be enough to initiate some sort of crisis of consciousness?

“There’s an assumption that seeing atrocity will animate you to respond in some way.... How many images will be enough to initiate some sort of crisis of consciousness?”

One example that comes to mind is the video of George Floyd’s murder, which sparked the Black Lives Matter protests a few years ago.

Every once in a while, there is an image or video that produces a kind of flash point. That’s part of my interest as an instructor and a researcher. How do we produce the piece of evidence that initiates something? It’s a hard question.

Is your approach to teaching artists and designers different than how you’ve taught in the past?

Well, this is my first time teaching, but it’s interesting that I’m talking about “the gaze” with people who are creating imagery and thus directing the gaze. It’s a bit nerve-wracking but also very exciting!

—interview by Simone Solondz

January 17, 2023