Faculty, curators and librarians come together for a semester-long seminar on decolonization that builds on the institution’s commitment to advancing social equity and inclusion.

Five Questions: Christopher Roberts

Last year RISD hired a cohort of full-time faculty members focused on race, colonization, decolonization, post-coloniality, cultural representation and material practices of resistance. The educators who joined the community as part of that “Race in Art & Design” cluster hire initiative began teaching at RISD in the fall and have graciously agreed to share their unique pedagogical approaches in this series of Q&As. In this interview, we hear from Theory and History of Art and Design faculty member Christopher Roberts.

Can you please say a little bit about yourself and your areas of academic focus?

My areas of research and expertise deal with the myriad ways that haunting and commemoration are wrapped up in Black geographies of memory and forgetting. The work is entwined with Black people the world over but has an emphasis on port cities in the US that anchored the transatlantic and domestic slave trades. I try to unravel how those themes emerge in relation to monuments, maps, archives and museums. My research leaves me both imagining and wrestling with questions of resistance, decoloniality, abolition and fun.

What attracted you to RISD?

This is my third year here. I was a post-doc for a couple of years. What appealed to me about this opportunity was being able to bring my whole self to the job. I have worked in museums and art galleries for more than 10 years and collaborated with a lot of artists. As an academic, I’ve done archival research, scholarly work, writing and theoretical work. RISD presented an opportunity to bridge those different worlds, to bridge my interests in arts and scholarship.

“What appealed to me about this opportunity was being able to bring my whole self to the job.”

What classes did you teach in the fall semester? And what challenges and opportunities do you face teaching through the lens of decoloniality?

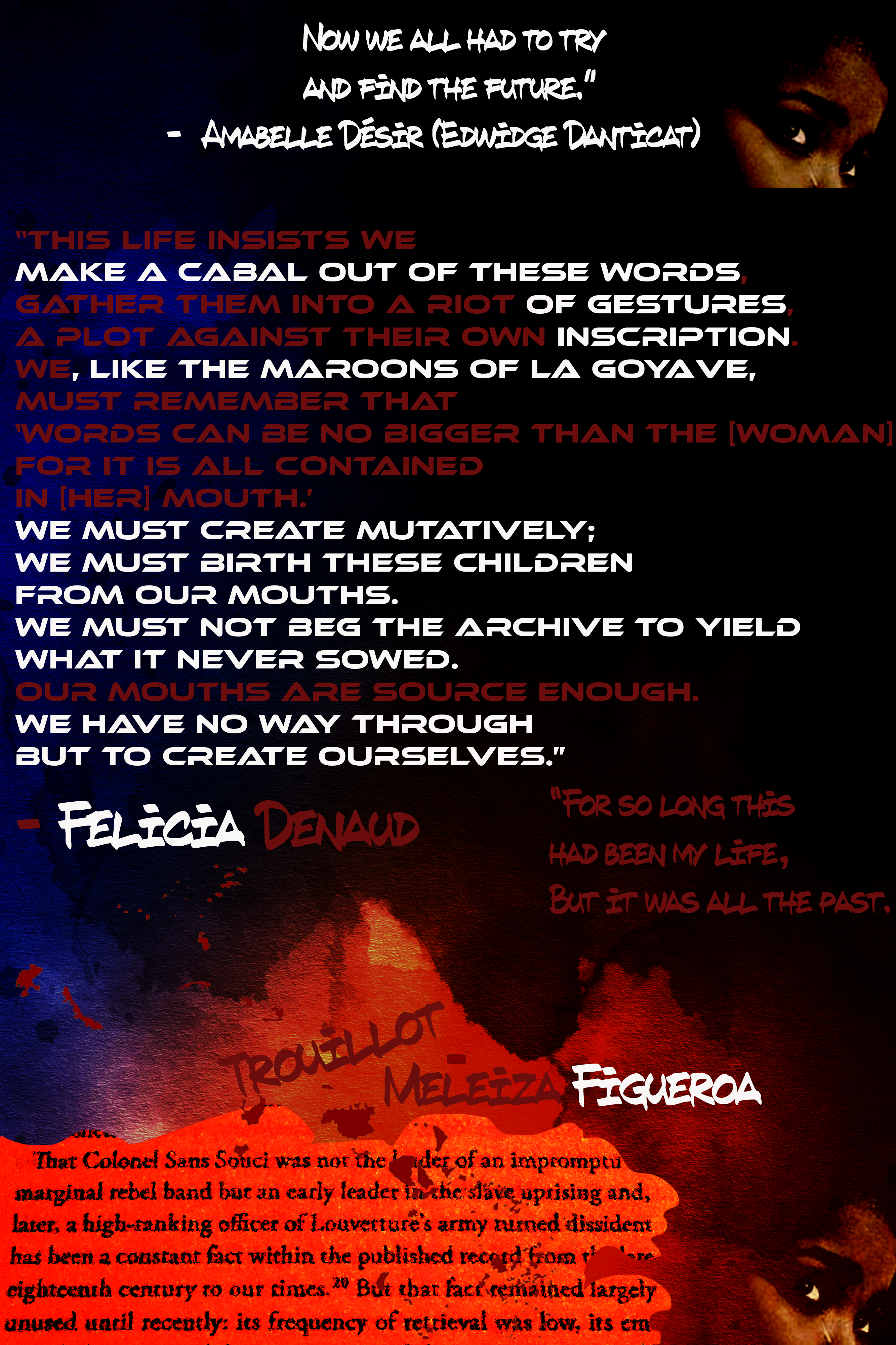

I taught a Theory and History of Art and Design course called Humanity or Nah? that deals with Blackness, gender resistance and memory. I was able to build on some of the larger questions I take up in my research that orbit around how Black people navigate a world where we are constantly compelled to make the case for being human in a society that has already designated us the constitutive abjection of humanity.

We read work by such scholars as Sylvia Wynter, Zakiyyah Iman Jackson and Alexander Weheliye and visited the Defying the Shadow exhibition at the RISD Museum. We spoke with the curator, Anita Bateman, to learn more about how different Black artists have approached the dilemma of Blackness and humanity in their practices.

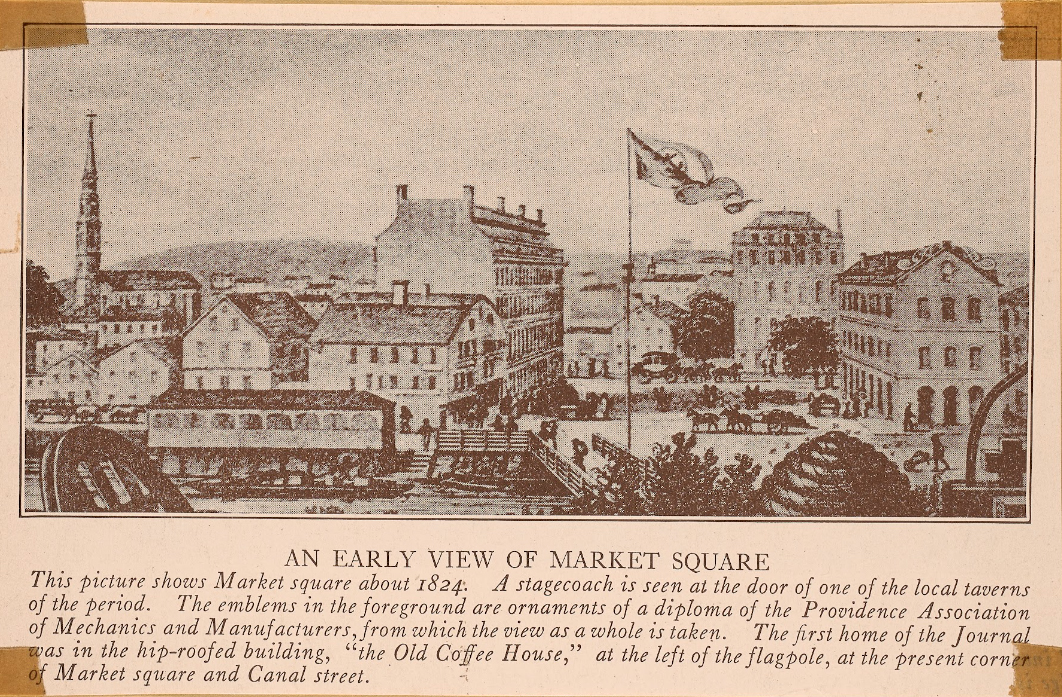

I also teach in the Experimental and Foundation Studies division, collaborating extensively with Spencer Evans and Cheeny Celebrado-Royer on mapping and memorialization projects. Using Silencing the Past: The Power and Production of History by Michel-Rolph Trouillot as reference, we studied representations of conquest in the RISD Museum, specifically the so-called “event of discovery” in 1492, Christopher Columbus—how that’s memorialized, some of the problems with that and how students can act as artists to disrupt the narrative arc of “discovery.”

What’s the most important thing you hope students will learn in your classes?

I hope they embrace a level of disruption within their educational experiences, that they understand that if the way things have always been is totally fine with them, then there’s a problem. Some things need to be shaken up. I hope they feel empowered to engage with the world around them and feel affirmed to continue to do the work they want to do, without pleasing the constituencies that have historically held power.

“I hope students embrace a level of disruption within their educational experiences—that they understand that if the way things have always been is totally fine with them, then there’s a problem.”

What is your take on RISD’s current state in terms of social equity and inclusion? What would you like to see the college focus on moving forward?

If I had to pin down on one thing, I think it’s about follow-through, turning rhetorical gestures into something that approximates a transformation or shift, whether that’s continuing to expand the number of Black, Indigenous, Latinx and Asian instructors and students, connecting to Providence or accounting for the history of the institution and its entanglements. It comes down to an ability to understand that as an institution that has largely benefitted from a grim history around these issues, the answers may come from those same people who have been historically left out or marginalized. The answers might be in places the school is not used to going.

—interview by Simone Solondz

Read the whole series and learn more about RISD’s commitments to Social Equity and Inclusion.

January 26, 2022