The Brooklyn-based artist known for exploring the connections between humans and tech discusses the inspirations driving their evolving practice.

RISD Sculpture Department’s Digital Fabrication Lab Offers Innovative Approaches to Making

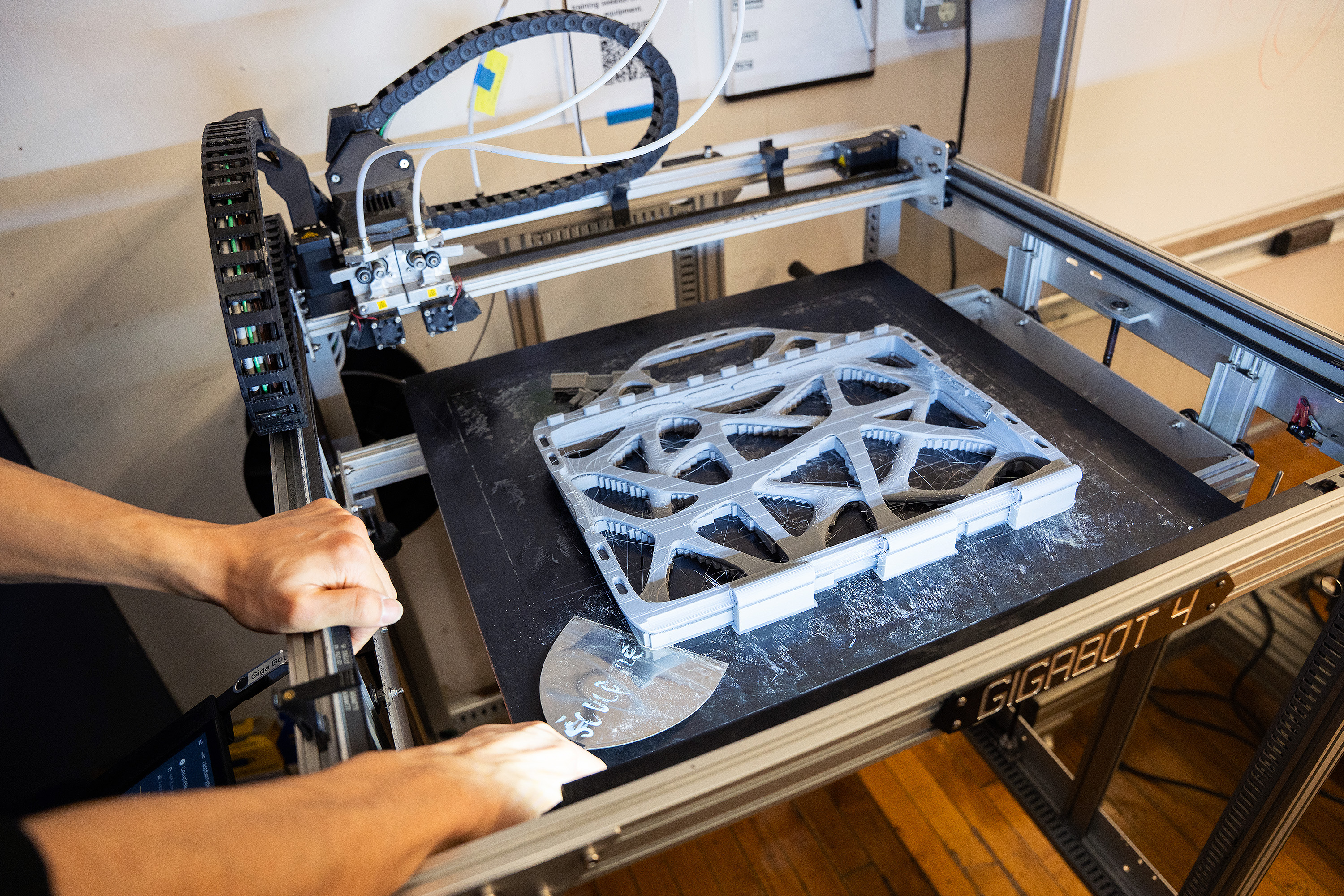

Over the past five years, the Sculpture department’s digital fabrication facilities have expanded significantly with the addition of such high-tech tools as a Gigabot 4 large-format 3D printer, a UR5e robotic arm, CNC machines, a laser cutter, an upgraded vacuum former, and multiple LulzBot Workhorse 3D printers. These tools allow students to integrate digital technologies into their sculptural practices, shaping how they conceptualize and produce work.

“Students are encouraged to experiment and iterate with these contemporary modes of making, integrating digital fabrication into their individual studio practices in ways that align with their artistic intentions,” says John R. Frazier Award-winning faculty member Gail Dodge MFA 15 SC, who also maintains the lab. “This technological fluency fosters a hybrid approach in which digital and analogue processes intersect to produce new aesthetic and conceptual outcomes.”

Dodge and fellow Frazier Award winner Ben Jurgensen collectively teach a range of electives focused on digital fabrication—from additive and subtractive processes to open hardware, robotics, and introductory digital tools. The curriculum integrates digital technologies with traditional and contemporary sculptural practices, including woodworking, metalwork, casting, video, installation, and performance.

“Our approach requires one-on-one attention and support, creating a strong feedback loop for students as they work through ideas and giving them a real sense of how they might incorporate these tools into their studios and practices pre- and post-graduation,” Jurgensen says. “Proficiency with 3D modeling and digital fabrication tools allows for quick development and iteration of ideas that lead to informed fabrication decisions.”

Students also learn CAD within these electives along with 3D capture techniques using the department’s non-contact 3D scanner and photogrammetry workflows. This allows them to bring existing forms into digital space, for example by scanning a sculpture or figure, modeling from or transforming it in CAD, and then outputting to a CNC machine or 3D printer.

Senior Ray Swartz 26 PT was initially waitlisted for Dodge’s Subtractive course and is making the most of the opportunity before he graduates. His current project embeds halftone images collected from a queer archive with which he is connected into wooden panels using the large-format CNC machine. The series investigates themes of nostalgia, legibility, image circulation, and translations between analogue and digital materialities. “There’s no way I could have done this by hand!” he exclaims as he applies shellac to the panels.

“Our approach requires one-on-one attention and support, creating a strong feedback loop for students as they work through ideas.”

Elsewhere in the Metcalf Building, grad student Michael Prisco MFA 27 GD—a student in Jurgensen’s Additive course—is presenting 3D-printed letterforms to the class. “I’m trying to make defensive letterforms for our hostile media landscape,” he explains as he passes around samples of the spiky objects. “I played with Rhino, Blender, and Grasshopper and found Blender to be the most useful tool for this.” Jurgensen opens the discussion to the rest of the students before encouraging Prisco to “consider scale, modularity, and a sculptural approach” as he continues to iterate.

Fellow grad student Russ Fogle MFA 27 FD is also bringing digital forms into 3D space, in his case the flatly ornate vestiges of early video game culture. “I tried to stay as true as possible to the language of the early Internet,” he tells the class. Fogle says he’s having difficulty tiling a woodgrain finish on the frame of the mirror he’s working on, and Jurgensen suggests that he try printing it at different temperatures in order to create the desired effect.

The conversation is technical and also mutually supportive and fun. “When the emphasis shifts from perfection to play, students often become more confident and engaged,” says Dodge. “This mindset not only makes the technical learning process less daunting, but also opens space for deeper exploration.”

Top photo: Ray Liu 26 ID uses a putty knife to remove a digitally printed laptop case from the Gigabot 3D printer.

Simone Solondz / photos by Kaylee Pugliese

November 20, 2025